Like most issues that really don’t matter in our hobby, there is somewhat of a dispute over when and where the first philatelic exhibition took place. The first stamp shows that called themselves “philatelic exhibitions” began about 1920 in Europe. But there is considerable logic for allowing that the Centennial Exhibition of the United States (which took place in Philadelphia in 1876 to mark the hundredth anniversary of American independence) also had a significant enough philatelic component to call it a stamp show. The Post Office ordered examples of all United States postage stamps to be on display and sale during the show. And for issues that were out of print, reissues were made so that a collector could buy many items there that were not on sale before or since. Special stamp displays and special limited philatelic issues for attendees are two of the more important characteristics of stamp exhibitions. So if the Centennial Exhibition wasn’t the first stamp show, it was, to use philatelic jargon, certainly a forerunner.

The first shows that would look and feel like the ones today began about 1900 and grew out of club shows where more serious philatelists would display their collections. By 1910, a dealer’s bourse began to be added. Soon the viewing of great collections, often in competition, and the perusing of stamps for sale were intermingled, and the modern show format, changed little in over one hundred years, was born. In the earlier shows, the dealer bourses were viewed as a kind of necessary evil. Dealers would come and trade at tables they set up outside the hall, so bringing them inside and charging them for tables was just logical. Even today, clubs like the Royal Philatelic Society don’t allow dealer members, a remnant of the days when the lines between dealer and collector were more firmly marked than they are today. By 1930, however, it was clear that the dealer bourse was attracting more collectors to the show than were the exhibits. The opportunity to examine the stocks of hundreds of the world’s most active and knowledgeable dealers became one of the great draws of international stamp shows. In 1926, the FIP (in English the acronym stands for “International Federation of Philately”) was established to coordinate international exhibitions. Currently the FIP sponsors two or three shows worldwide each year. The United States has an international show every ten years.

Attendance at stamp shows, both national and international, used to be tremendous. Stories of lines leading around corners and down side streets as collectors waited to get into shows sound like fantasies to us now. But I remember taking my girlfriend to Interphil, the US international show in 1976 (despite this, she later became my wife) and being very proud to be part of a hobby that could boast a quarter of a million square feet of exhibition space and hundreds of thousands of visitors. But besides the great collections on view and the hundreds of dealers and the chance to meet your philatelic friends, there was one other significant reason why early major stamp shows were so well attended—souvenir sheets.

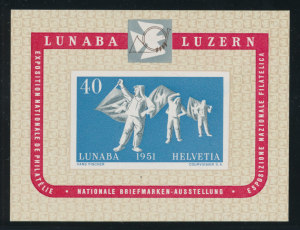

The first stamp shows often had postal patronage. After all, postal agencies sold thousands of dollars of postage stamps to collectors that would never be used. Postal accounting is non-accrual for stamp sales. This means that any stamps sold but not used do not have to be accrued as a liabilty on postal accountings. It’s a cash in and cash out system, so that any stamps sold and not used represent pure profit to the postal agency over and above the cost of printing. To encourage collectors to come to shows and collect and buy their stamps, beginning about 1920, postal agencies issued specially made souvenir sheets for shows. Usually a large format display of a current issue, these souvenir sheets were for sale, often at a small premium, at the show alone. Quantities that collectors could buy were often limited, sometimes only to one per person. As you can imagine, the prices of these early sheets rose tremendously, often within a few days of issue. Adding to their appeal was the questionable decision of Scott and the other major catalogers to give these sheets full catalog status and places in every album (after all, they had only a quasi-postal purpose, and similar types of stamps had been denied full listing status before. The fact that so many of the editors and publishers of the catalogs and their friends were at these shows and bought these sheets influenced the decision). The lines leading to the stamp shows of the 1920s and 1930s no doubt contained mostly serious collectors. But so too there were many who hoped to flip a couple of souvenir sheets for carfare and a small profit. The Swiss LUNABA sheet pictured above was the last of the philatelic souvenir sheets, of limited show issue, to become rare.