Probably no area of US philately has changed more over the last century than the collecting of US plate blocks. Ours was the first nation to collect plate blocks, and really is still the only country that does (Canadian collectors, UN collectors and Israel collectors have small plate block contingents, but these are derivative from US collecting, mainly appealing to Americans whose interest has migrated away from US philately and don’t represent an indigenous specialty of their own). We are so far away from it now that few are aware of why plate number collecting began in the first place. The great American experiment of outsourcing government services to private companies was tried before, and the postal story was one of the first. Before 1894, our Post Office contracted with private printers for printing and design of US postage stamps. Several companies were used through the nineteenth century. By the early 1890s, the Post Office was no longer convinced that the deal it was getting from the American Bank Note company was such a good one. The ABNC had been merged together from several smaller printing companies and for a long time had a near monopoly on the security printing market. The Post Office turned to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1894, and this began the 125 year practice of our government producing most of its own postage stamps.

The Bureau did all our government’s security printing including currency and bonds. They knew that they had the contract for a long time and wished to keep very careful records. Each stamp printing plate, as it was prepared, was numbered, and this number printed in the margin of the sheet. There was no intention to create collectible varieties for collectors, and for many years collectors argued over the best way to collect plate numbers. The very first collectors simply collected the plate number tab itself, and you still see a few collections today that have just printed plate numbers on tabs mounted consecutively (this isn’t as weird as it sounds—each plate number was unique to a certain plate, color, and denomination; so you can actually collect by set, as you would with stamps, by plate number alone). Within a few years of the first plate number stamps being issued in 1894, collectors were collecting them adjoining the stamp that they were issued with. A few years later saw the hobby expand to plate number strips of three (this is still the preferred collecting format for the great 2¢ issues of 1894-98 (Scott #248-252, 265-267, and 279B). It was only about 1910 that collector opinion coalesced around the concept of plate number blocks of 6 for flat press printed stamps and plate number blocks of 4 for rotary press prints.

The Bureau did all our government’s security printing including currency and bonds. They knew that they had the contract for a long time and wished to keep very careful records. Each stamp printing plate, as it was prepared, was numbered, and this number printed in the margin of the sheet. There was no intention to create collectible varieties for collectors, and for many years collectors argued over the best way to collect plate numbers. The very first collectors simply collected the plate number tab itself, and you still see a few collections today that have just printed plate numbers on tabs mounted consecutively (this isn’t as weird as it sounds—each plate number was unique to a certain plate, color, and denomination; so you can actually collect by set, as you would with stamps, by plate number alone). Within a few years of the first plate number stamps being issued in 1894, collectors were collecting them adjoining the stamp that they were issued with. A few years later saw the hobby expand to plate number strips of three (this is still the preferred collecting format for the great 2¢ issues of 1894-98 (Scott #248-252, 265-267, and 279B). It was only about 1910 that collector opinion coalesced around the concept of plate number blocks of 6 for flat press printed stamps and plate number blocks of 4 for rotary press prints. Plate number collecting began to decrease in popularity about 1980 when multicolored stamps meant numerous plate numbers in the margins, and collectors were unsure of the proper number of stamps that were going to become the accepted standard for each plate block. Finally, most stamps now are issued in full sheets of twenty, and the entire sheet is considered a plate block. This has led to a decline in traditional plate block collecting (and the interest in newer collectors in sheets has led to rising prices for older sheets as there are now collectors who wish to move their collections of plate blocks/sheets backward in time). Prices for classic plate blocks have, accordingly, languished. Further, earlier plate blocks are very difficult to find in the pristine quality that modern collectors are used to with newer issues and which they often try to demand as they move to acquire earlier items for their collections. Early plates don’t just require one stamp to be nicely centered to be in VF quality—they need all four or six stamps to be perfect. Further, handling over the years has produced separation issues that modern collectors find irritating. Plate blocks sometimes even separate on their own from simple album handling, and this can create a financial loss that many collectors find unacceptable. Never discussed too, is the fact that because plates are a multi-stamp format, they are impossible to regum convincingly (the fake gum would muck up the perfs between the stamps) leading to many hinged plates laying around which don’t meet modern standards (for those of you reading between the lines, yes, many early twentieth century stamps have been regummed to resemble NH. This has been done so convincingly in recent years that, seeing how often experts have been fooled in the past and how expertization standards have changed, many collectors find a hinge mark to be the best assurance of original gum).

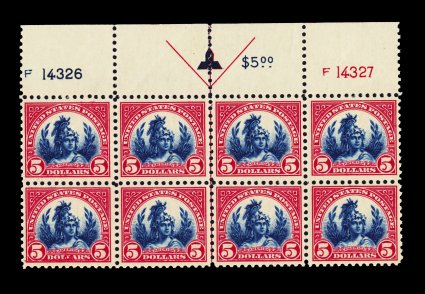

Plate number collecting began to decrease in popularity about 1980 when multicolored stamps meant numerous plate numbers in the margins, and collectors were unsure of the proper number of stamps that were going to become the accepted standard for each plate block. Finally, most stamps now are issued in full sheets of twenty, and the entire sheet is considered a plate block. This has led to a decline in traditional plate block collecting (and the interest in newer collectors in sheets has led to rising prices for older sheets as there are now collectors who wish to move their collections of plate blocks/sheets backward in time). Prices for classic plate blocks have, accordingly, languished. Further, earlier plate blocks are very difficult to find in the pristine quality that modern collectors are used to with newer issues and which they often try to demand as they move to acquire earlier items for their collections. Early plates don’t just require one stamp to be nicely centered to be in VF quality—they need all four or six stamps to be perfect. Further, handling over the years has produced separation issues that modern collectors find irritating. Plate blocks sometimes even separate on their own from simple album handling, and this can create a financial loss that many collectors find unacceptable. Never discussed too, is the fact that because plates are a multi-stamp format, they are impossible to regum convincingly (the fake gum would muck up the perfs between the stamps) leading to many hinged plates laying around which don’t meet modern standards (for those of you reading between the lines, yes, many early twentieth century stamps have been regummed to resemble NH. This has been done so convincingly in recent years that, seeing how often experts have been fooled in the past and how expertization standards have changed, many collectors find a hinge mark to be the best assurance of original gum).Still, for difficulty of the chase and rarity factors, plate block collecting still has a devoted corps. The stamp at the top is a perfect example why. It is Scott #402 and catalogs $70 mint and can be purchased in just about any quantity you want for $20-25 each. The plate above of this relatively common stamp catalogs $6,750 and is very rare. Combing our archives, I found that we have sold only three in the last twenty years. Many collecotors find that the thrill of the chase is what excites them about this hobby. For people like this, plate block collecting offers many charms.