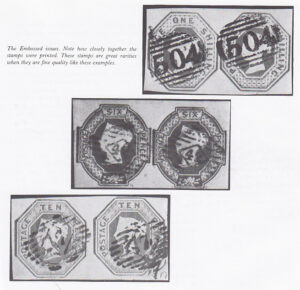

While the post office was experimenting with these perforations, some other stamps had been issued, caused primarily by increased public usage of the mails and Britain’s growing commerce overseas. Three stamps, all embossed Queen’s heads against colored backgrounds, include a one shilling issued in September of 1847 (#5), a ten pence (#6) issued in November 1848, and a six pence (#7) issued in March 1854. These stamps are among the most difficult in all of philately to get in perfect condition. In some places on the sheet, the designs actually overlapped, so that finding examples with any margins at all is well-nigh impossible. And they are often found cut to their octagonal shape, a condition much denigrated by philatelists. Unused examples are rarities.

The first two, #5 and #6, were issued on a paper that had double silk thread running through it, so that each stamp was printing on paper having the double thread line. This was done as an anticounterfeiting measure, the theory being that duplicating the silk thread would discourage would-be counterfeiters and make it easier to apprehend those who did try it. But the silk thread serves a valuable purpose for modern philatelists. The embossed issue was also used on envelopes that were issued by the government, called postal stationery, which, in this case, are not nearly as scarce as the stamps. Philatelic swindlers would be tempted to clip the embossed stamp off the envelope and sell it as a postage stamp, were it not for the fact that the lack of silk threads would make this deception obvious. The six pence (#7) does not have a silk thread but was issued on paper watermarked continuously with the letters “V.R.” — Victoria Regina.

The first perforated issue of stamps in the world came out in 1854. Each improved perforating machine based on Henry Archer’s design was able to perforate 400,000 stamps per day. They were run by steam, and at first five machines were employed, giving the printing office the capacity to perforate 2 million stamps per day. The early experiments with perforations and small die types account for the next fourteen Great Britain catalogue-listed stamps issued over the ensuing four years. It should be noted that until recently the British Post Office’s stamp-issuing policy was probably the most conservative in the world. Indeed, the One Penny 1841 remained in use until a perforated version appeared. Some die variations in the mid- and late 1850s make for collectable varieties, but the 1864 One Penny stamp was the general postage stamp for the nation for sixteen more years. Comparable length of duty for the design type does not exist for either United States or Canadian stamps.

The first perforated stamps were perf gauge 16, and it was soon discovered that perf 16 gauge perforation separated far too well. The closeness of the holes meant that postal clerks had to be extremely careful lest the stamps should tear apart in their drawers. Even with care, the stamps were difficult to work with and to transport in quantity. A little later a gauge perf 14 was tried, which spread out the holes a bit; apparently both perf 14 and perf 16 were used coincidentally. Many perforation varieties exist of these early perforated stamps, including double rows of perforations, partly perforated stamps, and even completely imperforated stamps. Furthermore, the centering of the perforations on the stamps– or, as philatelists usually misrefer to it, the centering of stamp within the perforations– was wretched. It is almost impossible to find one of these early perforated stamps in which the perforation holes do not touch the design of the stamps. Still, the innovation was well received. The public cared little about how its stamps were centered. And there were not enough collectors yet to make the complaints that render the quality control job at the post office so unpleasant.

Finally, in 1855, Perkins, Bacon & Petch, the printers of Great Britain’s postage stamps, wrote to the Inland Revenue, which administered stamp printing, and said it was time that a new die was made for the One Penny stamp. The new die would have more deeply cut lines, which would show the Queen’s head off to finer contrast. As an added bonus, the deeply cut die would last longer, and so require that less plates be made. Apparently, the government was also ready for a change. In less than a week it responded that Perkins, Bacon & Petch should begin preparing the new die, which was issued shortly thereafter.