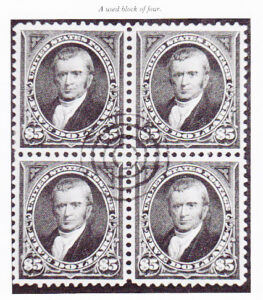

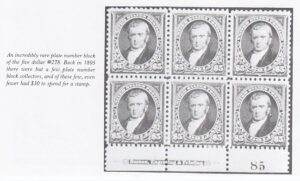

In 1894, the Post Office Department began having its stamps printed for it by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP), the same government agency that printed money. The BEP had competed for the 1894 contract, and not only was its price lower, but there was the added convenience of having the work done in Washington near the Post Office Department, allowing greater responsiveness to department needs. The 1894 set contained the same portraits of prominent Americans as the 1890 set, with some values changed and with new values added up to $5. Triangles were added to the upper left corner. Fewer than 6,000 complete sets were sold; of the $5 value, many were used for postage and destroyed. This set is a genuinely undervalued one. As these were the first stamps produced by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing – a good printer but new to stamps – the quality of production, and especially the alignment of the perforations, was poor. Expect to pay great premiums for perfect examples.

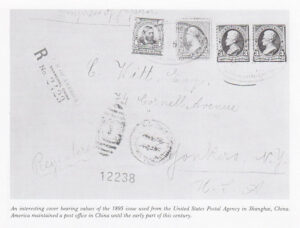

In 1895, the Post Office Department ordered the 1894 set to be printed on watermarked paper, which means that philatelists treat the 1895 set as a completely different issue. The paper was water-marked in the sheet with a large repeating double-lined watermark, “U.S.P.S” (United States Postal Service), 16 millimeters high, in a continuing pattern across the sheet. Stamps frequently have parts of one or more letters watermarking them. These stamps were watermarked because some counterfeits of the 1894 issue had shown up and the postal authorities thought they could better discourage counterfeiting if they printed on watermarked paper. This watermark continued on all stamps until 1910, when a different watermark pattern– using the same letters, but in single line– was used until 1917. Since 1917, no United States stamps havebeen ordered on watermarked paper.

Part of the reason for the scarcity of the 1894 issues is the quick advent of the 1895 watermarked stamps. The previous issue was in use only a short time and was removed from sale without much warning. Then, as now, collectors usually bought their high-value stamps from the post office at the end of a run rather than the beginning. Why would a collector tie up $5 or more (when $5 bought the average family food for a week, not just a skimpy lunch) for a stamp that would be on sale for years when he could buy it as easily just before it went off sale? many rarities are created in this way; that is, when the post office quickly and without the usual warning takes an item off sale and collectors who have been waiting to buy it are caught empty-handed. It would seem prudent, then, to buy your high values early in the run. But by the same token, many dollar-value stamps are kept in the post office for five or ten years. T tie up money in quantities of high-value stamps that will show no increase in value until they are taken off sale is not prudent either.

The 1895 watermarked issue (#264-278) is far less scarce than the 1894 unwatermarked, with over 25,000 of the $5 value (#278) distributed.

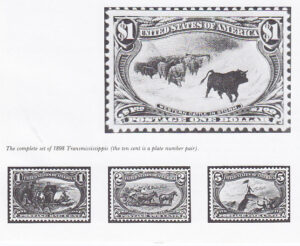

The 1898 Transmississippi issue (#285-293) is today one of the most popular issues with collectors. The $1 “Cattle in the Storm” (#292) has been voted by serious American philatelist as the most beautiful stamps this nation has ever produced. But to contemporary collectors, still stinging from the unnecessarily high values of the 1893 Columbus set, the issuance of this set seemed positively Machiavellian. The Transmississippi issue contains values up to $2, and though it is listed as having 56,000 complete sets printed, and unknown quantity, but probably 30,000, were unsold and destroyed. For some odd reason, certain values of this set (especially the 4 cent, 10 cent, and $1) were produced well centered and can be purchased in excellent condition without mortgaging the house. But other values (specifically the 8 cent and $2) nearly always are off center. They were produced at the same time and place, so this is one example of many in philately of experience making a mockery of logic.