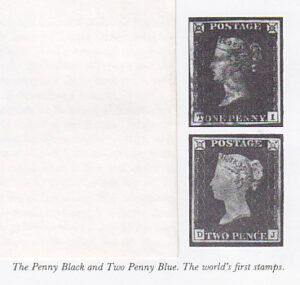

Great Britain was the innovator in postal and philatelic matters. It produced the first postage stamps (see Chapter 2), but the color of the one-penny stamp, the Penny Black, was soon considered unsuitable. The black made it difficult to cancel effectively and the post office in Britain, like its counterparts throughout the world, feared that its stamps were being cleaned and reused.

Great Britain was the innovator in postal and philatelic matters. It produced the first postage stamps (see Chapter 2), but the color of the one-penny stamp, the Penny Black, was soon considered unsuitable. The black made it difficult to cancel effectively and the post office in Britain, like its counterparts throughout the world, feared that its stamps were being cleaned and reused.

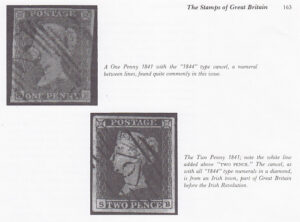

In late 1840, the decision was made by Rowland Hill and other post office officials to change the colors of the British stamps. A light red brown shade was chosen for the none-penny stamp, and after experimenting with different colors for the two-enny blue, it was resolved to continue printing in blue. A line was added to the design above the value tablet “TWO PENCE,” so that this printing could be distinguished from the previous one. The one-penny red stamp was the first-class-rate stamp for Great Britain for thirteen years. About 2 billion were printed and sold, a quantity that has assured their being quite common even today. But the Penny Red, as it is called, is a popular stamp, and many collectors own numerous copies as they attempt to plate the stamp, or to collect it by position using the corner check letters. A collector attempting a positioning needs 240 different Penny Reds. The Two Penny Blue 1841 is far scarcer than the Penny Red, indicating the scarcity of double-rate letters, but even of this stamp, 90 million were printed. Two major types of cancellations are known on the 1841 issue: Maltese Cross cancellations and, beginning in 1844, a cancellation called the “1844” type cancel. The “1844” cancels are far more common and are oval-shaped, with numerals inside them. The numerals correspond to an assigned numbering system representing the post office where they were cancelled.

In August of 1841 the first realistic suggestion for the separation of postage stamps, besides the individual use of scissors, was proposed. A correspondent wrote to Rowland Hill suggesting that a deep line might be cut between the stamps when they were engraved, so that in the process of printing, the paper would be pressing into the cuts and each stamp could then easily be parted from the others. But Hill was too preoccupied in advancing his postage stamp innovation and defending his scheme from ruffled bureaucrats to pay the idea much heed. And Hill never thought much of perforations anyway.

In 1847, Henry Archer took up the plea for separations on the sheet, and demonstrated his new invention– a separating machine– to the post office officials later in the year. His early method was to use rouletting (see page 34). Archer’s idea was an innovative one, though it soon became apparent to him that rouletting was not practical for large-scale stamp issuing. The cutting knives wore quickly, and they so cut the bed beneath the stamp sheet that replacements became inordinately costly. In late 1848, Archer abandoned the rouletting idea altogether and developed a perforating machine that produces perforations which both appear and function exactly as on our stamps today. Several trial perforations were made in the ensuing years and some were released to the public. Finally, in 1852, the government paid Archer 4,000 pounds for his machine and his patent rights, a sum Rowland Hill considered wildly extravagant. However, if one were to pro-rate the cost of the patent over the number of times Archer’s machine has been used since, the post office purchase must surely rate as one of the great bargains of all times.